Have you ever developed a sense of friendship for someone who doesn’t know you; say, a television or sports star? You feel you really know them, but they’ve never heard of you. You might pass them on a busy street or at a crowded airport, and wonder why they don’t respond to your smile and nod of greeting. Historians develop similar friendships which are just as one-sided, but often that feeling of knowing someone well develops with a person long dead.

Valda Kelly, 1894-1918

One such friendship developed for me in the Archives of St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne while researching the history of nursing. This ‘friends’ name was Valda Kelly. Tragically she died when very young while nursing patients with the Spanish flu.

The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was the most devastating epidemic in recorded history. Worldwide it is thought to have killed an estimated 50 million people, although some experts suggest the total might actually have been twice that number. More died during the pandemic than in the course of the entire First World War, some think possibly more that the First and Second World Wars combined.

The virus struck the very young and elderly and, appallingly given the number of young who died in the war, was most deadly for those in the 20 to 40 age bracket. At the time epidemiologists knew little about the behaviour of virus’, and one doctor described the “diffuse anxiety, [and] sensation of some indefinable horror” caused by the pandemic in a community. The outbreak hit Melbourne in December 1918. Local authorities were aware of the devastating effects of the disease in Europe, and took precautions to limit its impact. Strict procedures were in place before the virus attacked. The border between Victoria and New South Wales was closed; public meetings of twenty or more people were prohibited; travel in long distance trains was restricted; loitering ‘under the clocks’ at Flinders Street station was strictly forbidden; and people were encouraged to wear masks in public. In a desperate effort to stave off the virus, the disinfectant phenyl was also poured into ‘two or three carts used for sprinkling [Melbourne] city streets.’

Hospital beds in Great Hall during the influenza pandemic, Melbourne Exhibition Building Carlton, c.1919

To what degree these precautions controlled the spread is open to conjecture. Still, and probably because it was summer, Australia escaped relatively lightly compared to India, China and Europe. About 12,500 died nationally from the pandemic; around 30 percent of these were Victorians. So great were the number of people taken ill that the Exhibition Building was converted into an emergency hospital between February and August 1919. Around 500 beds were initially set up inside the building, for it was originally intended the temporary hospital would only deal with convalescing patients. But within a few days of opening on 4 February under pressure of demand the scheme broke down and bed numbers quickly increased to 2 000. This is what it was like in Melbourne in early 1919 when, in her final year of training, Valda Kelly began nursing Spanish flu patients.

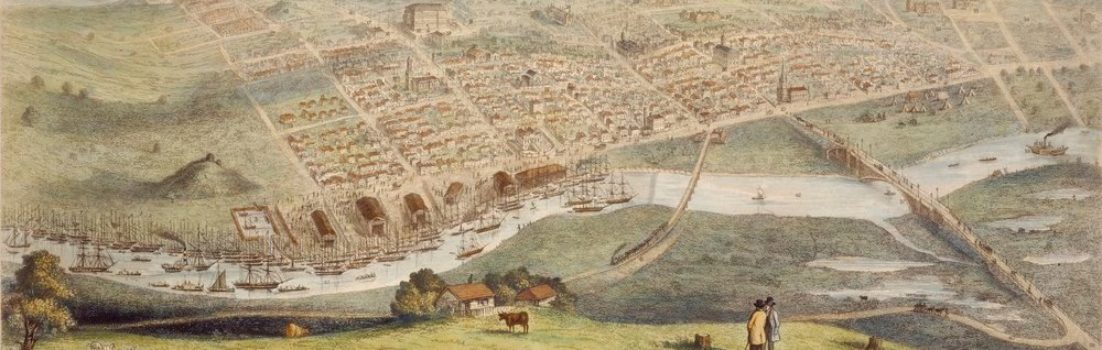

St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, c.1911. The hospital was virtually unchanged when Valda Kelly commenced her in training 1916

Valda had started her nursing training at St Vincent’s in November 1916 – maybe she was fired by patriotic zeal and an urge to contribute to the war effort, just like the boys her age who were volunteering as soldiers. There were even suggestions Valda was unofficially engaged to one of those soldiers. Hearsay also connects her to a soldier-boyfriend who died at the front, but without his name verification is impossible.

The first wave of the pandemic hit Melbourne in January 1919 and proved to be the most virulent, the number of infected reaching their greatest height in the second week of February. As a trainee nurse Valda was perhaps more susceptible than the average 24 year old living in Melbourne at the time. Typically she worked long hours – usually from 7am-7pm, 6 days week – but during the pandemic her working hours were even longer and the tasks performed more challenging as well as unremitting, for ambulances arrived constantly with two or three patients, sometimes bearing corpses. It was in the early weeks of the pandemic that Valda succumbed to the virus.

Female Ward, St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne c.1918. Judging by the absence of masks, this was not a Spanish flu ward.

The disease struck with amazing speed, overwhelming her weakened immune system and causing uncontrollable haemorrahging that filled her lungs – she probably eventually drowned. In an attempt to curtail the spread of infection visitors were forbidden. So on the 14 February 1919, Valda died in isolation without anyone permitted to comfort her nor bid a farewell.

Valda was not the only nurse infected at St Vincent’s. At about the same time she took to her hospital bed the hospital’s registrar reported 23 nurses ill from the virus. Over at the Melbourne General Hospital (Royal Melbourne Hospital), the superintendent reported 39 nurses had been infected and, as he added, eight were seriously ill; one died five days before Valda on 9th February.

Valda was the only fatality among the St Vincent Hospital’s health-workers. A section of the 1919 Annual Report was devoted to describing the impact of the pandemic on the hospital; Valda’s death was recorded as an addendum that noted: … one case among the nursing staff was fatal.

Valda’s death devastated many, especially her family. Friends like Carrie O’Grady mourned her passing too. Carrie expressed her grief in the death columns of the Argus, dedicating the notice: In loving memory of my chum, Valda (nurse) Kelly.

Despite still feeling saddened by her early death I also feel a great admiration for Valda and her fellow nurses’ for their bravery during the pandemic. Their efforts and the care provided at the Front during the war by 1000 or more nurses from Victoria resulted in a heightened respect for the selfless role nurses played. As MLA John Percy Jones observed, ‘There is no profession more important to the community … than the nursing profession.’ His comment was made during parliamentary debates prior to passing the Victorian Nurses Registration Act in 1923. The Act recognised the vital role played by nurses such as Valda Kelly.

The observance of Australia Day on 26 January, however, is much more recent.

The observance of Australia Day on 26 January, however, is much more recent.